It is something of a mysterious art. By nature motorcycles and riders are not the most aerodynamic of vehicles on the road so what do KTM do to maximize this area of their R&D and how does it fit in with the design of the orange bikes? We delved into the quiet and complex depths of engineering at Mattighofen to ask …

Think of aerodynamics and motorcycles. Most people would conjure an image of a wind tunnel and a tucked-in rider on a sports bike. Some might revert to MotoGP and the weird and wonderful experiments with winglets through the last five years. A few more might remember well the ‘dustbin’ fairings of the 1950s (significant for straight line speed and gains but a nightmare for cornering and lateral forces). ‘Aerodynamics’ sounds flash and intriguing but inside KTM, and probably most other manufacturers, the quest for efficiency revolves principally around comfort and performance. “It is a lot of testing … and it is different to what you expect of aerodynamic work and maybe what the customer thinks,” reveals Nico Rothe, Head of Project Support Street. “Maybe you only think of performance or a wind tunnel. You don’t think of the pressure on the chest or the head of the motorcyclist and many other things.”

Rothe heads a small and special team in Austria with decades of experience, even touching MotoGP with project and concept chassis and development research from the company’s first dabble with the premier class of Grand Prix at the beginning of the century.

“80% of what we do [now] is comfort development and what the rider feels on the bike. Our goal is to make it comfortable and safe,” he says. “The truth is that most of our testing is done on the test track. For standard road development we do 300-400 tests of several versions of the bike to get comfort where it should be. It starts off as being quite rough in order to get the proportions of the fairing and then we go into very small details when it comes to sound and aero-acoustic noise reduction. Noise reduction is 50% of our work. It is noise – not sound – and to get it in a direction where it is not too annoying.”

Thinking about design

Rudimentary knowledge of KTM’s portfolio means a slew of Naked Bikes, ADVENTURE machinery and, of course, offroad models. Then from small cylinder sports motorcycles to electric bikes and race replicas; the collection is wide and diverse and the design and aerodynamic implications follow suit. How do Rothe and his guys fit in?

“Talking about aerodynamics and design is like the saying ‘what comes first? The chicken or the egg?’ But we let the designers start because we could not give them a perfect aerodynamic shape and say ‘now make a design from that’ … which is actually how MotoGP works! The race guys have their aerodynamic concept and the fairing is very, very functional and then the designer comes in and is allowed to change it a bit to make it look like a KTM. Our job as aerodynamic specialists when it comes to Street bikes is to make the initial Kiska design work … without changing it.”

“A lot of ideas come from the designer and they often think a bit differently than a technician. There are some aesthetic rules about how surfaces should be but you can play a lot with the angle, with the depth, with certain steps. We can give a concept of airflow and they will be able to interpret that and make it look good. Something like MotoGP, which is performance aerodynamics, changes very frequently and even on Street models – which is comfort aerodynamics – there can be many variations year-on-year. Calculating figures for Street bike comfort is much different to working out drag values in MotoGP; it is a different world of development.”

Tools and talent

Rothe goes into more detail with the practicalities of the job. In addition to the complexities of wind tunnel work that involves high cost due to the knowledge of the specialists required just as much as the hardware and software itself. “We have a modified test bench where we can do the airflow for cooling and a lot of time and work is spent there”. The actual day-to-day labor of aerodynamic R&D means getting very hands-on.

“If we are talking about comfort aerodynamics then it is about feeling. It is hard to put feeling into figures but I’m sure in ten years we’ll have even more possibilities to measure that. In the wind tunnel you can put the helmet and body in certain positions to measure forces and dynamic forces to get different levels but that will never replace an actual rider’s feeling and feedback. Racing in MotoGPTM is an example: data recording will give you a lot but so does the feeling of the rider and it is difficult to get that from any kind of data. Comfort aerodynamics is the same.”

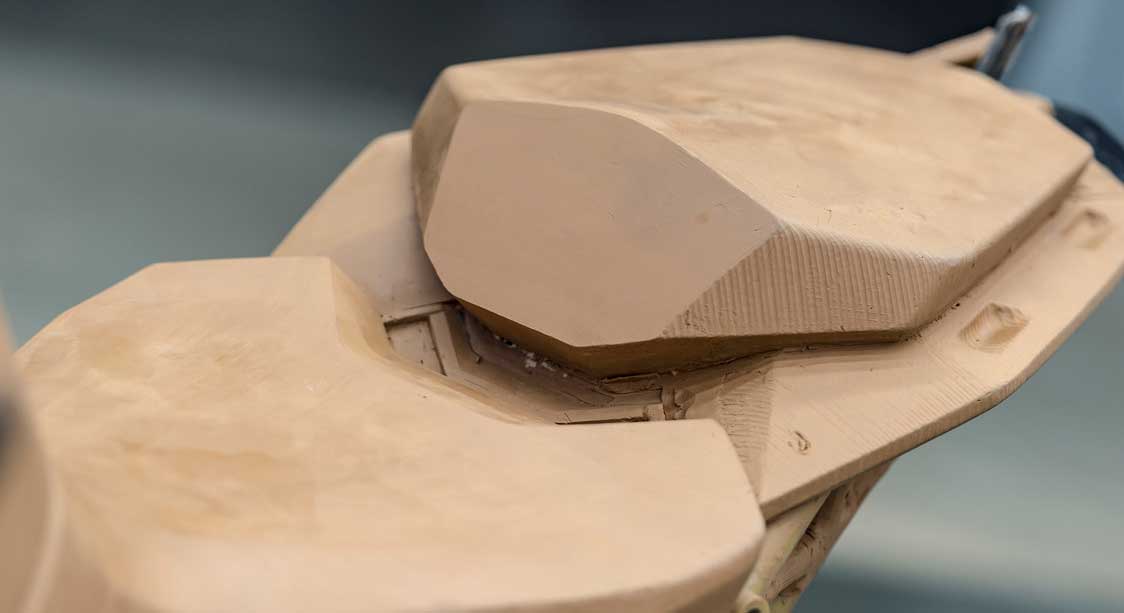

“You can play with clay to improve small areas,”Rothe goes on. “Usually we work with high-end 3D printed prototype parts but sometimes our working tools are a glue gun, tape and a grinder. Sometimes we are like model makers!”

What about specifics? And how is the aerodynamic specialist implicated into the production ‘journey’ of a bike? “The windshield is the most important part for noise and sound development; it is like fine-tuning a carburetor. You cannot say the aerodynamics are frozen with the first prototypes. Something like the frame will be changing all the time. We are also one of the last ones to sign off: we are there right from the beginning until the very end. Of course we have some milestones in a project where we have to say ‘this is ready’ so other people can do their work but the small stuff goes on.”

“In the beginning of development you should freeze a proportion of the bike quite early; if you start to mold the fuel tank a lot then it pushes the air up and can make things very difficult. We have certain steps and overall we start with wind protection and the size of the parts has to be defined at an early stage. If that doesn’t work and sometimes the parts don’t sync together then you find that out the hard way with many tests to understand what is going on. The general airflow to the body has to work, and then you start with details like spoilers and lips to optimize the sound and head turbulence.”

“In the product definition there is a certain level of requested aerodynamic comfort and sometimes there are height restrictions for homologation or even for size for packaging and transportation. And to allow a production bike to fit every customer is not so easy,” he adds, “but each rider can influence the aerodynamics on the bike with standard adjustments such as footpegs and handlebars, and on premium bikes we have adjustable windscreens and seats, as well as all the KTM PowerParts elements.”